PAPER ONE: SEPARATE CHEMISTRY

A GCSE revision page covering all of the separate chemistry content for Paper 1 topics transition metals, corrosion vs rusting, electroplating, concentration & titration calculations, yields & atom economy, dynamic equilibrium, fertilisers, chemical cells and fuel cells with practical examples..

CH159: Identify the properties of the transition metals

Physical Properties:

- Malleable (can be hammered into shape)

- Ductile (can be stretched into wires)

- Good conductors of electricity and heat

- Shiny when polished.

Transition metals usually have higher melting points and densities than metals from groups 1 and 2.

There are exceptions though – mercury is a liquid at room temperature!

Chemical Properties:

One of the main chemical properties that makes transition metals different to those in groups 1 and 2 is that they form colourful compounds - such as iron (II) oxide, which is a red/brown colour.

Transition metals are used as catalysts (which speed up a chemical reaction without being changed chemically)

- Iron is the catalyst used in the Haber Process.

- Iron (III) chloride, FeCl3, is used during the manufacture of PVC

CH160: Explain the difference between corrosion and rusting

Corrosion:

Corrosion is the weakening of a metal over time through rusting, oxidation, or chemical reactions.

The more reactive a metal, the more quickly it corrodes. This is because they lose their electrons faster. Some metals, such as gold, do not corrode at all.

Some metals, such as aluminium, will form a layer of tarnish when they oxidise – stopping oxygen from getting to the surface of the metal.

The statue of liberty is another example of tarnish protecting the metal from corroding further.

Rusting:

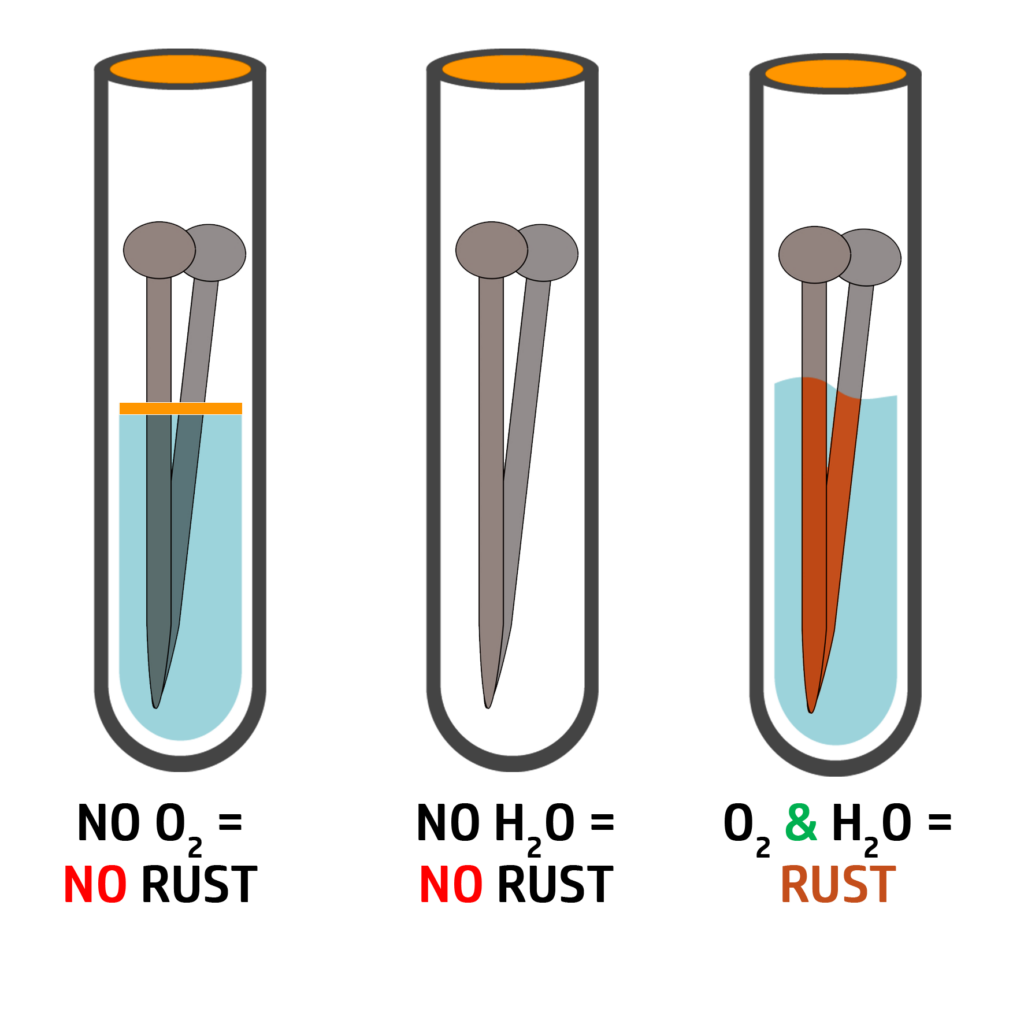

Rusting only occurs in iron. Iron reacting with oxygen is the same as corrosion.

For iron to rust it needs oxygen and water.

As you can see on the right, without oxygen and water, the nail does not rust.

iron + oxygen + water → hydrated iron oxide

CH161: Explain how to prevent corrosion / rusting

There are several ways you can stop rusting and corrosion from occurring:

1. Removing Oxygen: Storing the metal in argon / nitrogen

2. Physical Barriers: Coating the metal with paint, oil or plastic.

3. Sacrificial Protection: Putting a more reactive metal, such as magnesium, over the iron.

The oxygen will then react with the more reactive metal, instead of the iron, stopping the iron from rusting.

The more reactive metal loses its electrons (oxidises) faster.

4. Electroplating: Using electricity to put a thin layer of a less reactive metal on to the one you want to protect (See CH162)

5. Galvanizing is a combination of different rust protections. The iron/steel is coated in a thin layer of zinc. This provides a physical barrier and sacrificial protection.

CH162: Explain the process and uses of electroplating

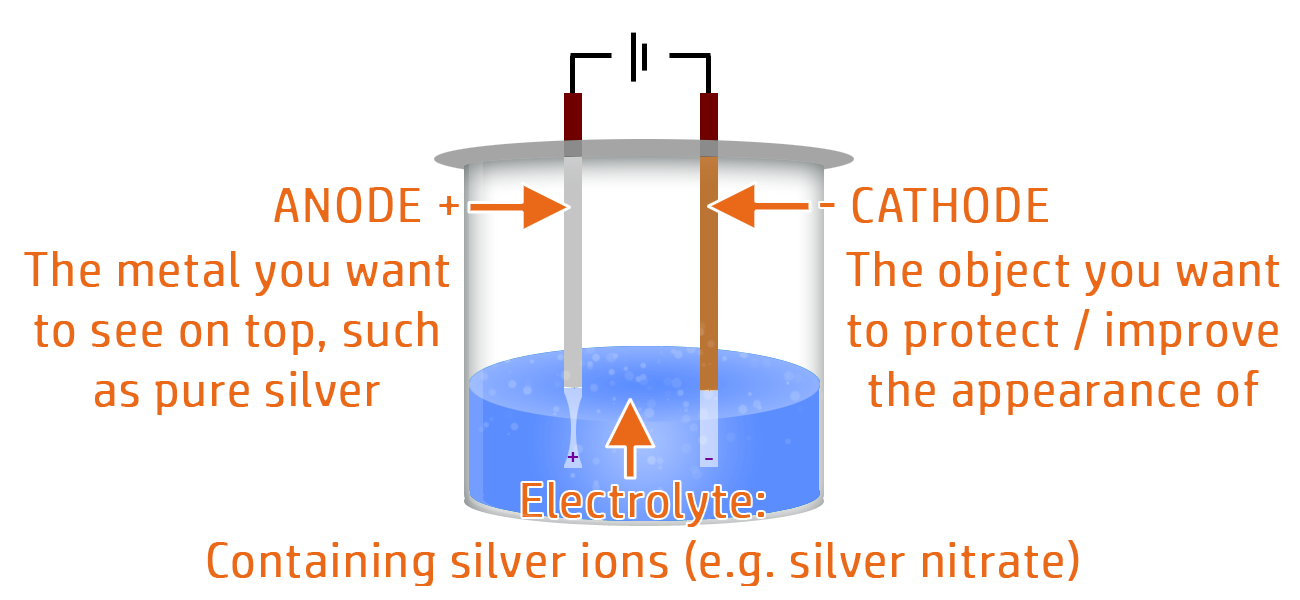

Electroplating uses electrolysis to put a thin layer of a less reactive metal onto the object you want to protect.

- The cathode (negative electrode) should be the metal you want to protect or improve the appearance of.

- The anode (positive electrode) should be the metal you are using to protect it.

- The electrolyte (ionic liquid) should contain ions of the protecting metal.

Example: Explain how electroplating can be used to coat a spoon in silver. (3)

Part 1: Attach the pure silver to the anode. The silver atoms will turn into positive ions by losing electrons (oxidised) and move through the electrolyte to the cathode.

Ag → Ag+ + e-

Part 2: The electrolyte will contain silver ions as well so that the ions are free to move.

Part 3: The silver ions will move to the cathode, where they will gain their electrons back (reduced) and turn back into metal atoms - coating the metal you want to protect.

Ag+ + e- → Ag

CH163: Explain how alloying makes metals stronger

An alloy is a mixture of a metal and another element – usually another metal.

Pure Metals:

In a pure metal, all the particles are the same size, forming a regular pattern / lattice.

This means that the layers can slide past each other – making them malleable, ductile, and SOFT.

Alloys:

In an alloy, the particles are different sizes.

This means that the layers cannot slide past each other.

This makes alloys much stronger than pure metals.

CH164: Explain the uses and properties of metals and their alloys

| Name: | Metal or Alloy? | Use: | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | Pure metal | Memory Chips | Excellent conductor of electricity.Soft and expensive. |

| Jewellery Gold | Alloy | Jewellery | Alloy of gold and copper.Stronger than gold but still attractive. |

| Copper | Pure metal | Wires and Pipes | Good conductor of electricity and ductile. Cheaper than gold. |

| Brass | Alloy | Plug Pins | Alloy of copper and zinc.Worse conductor, but stronger than copper. |

| Aluminium | Pure metal | Overhead Cables | Good conductor of electricity.Less dense and cheaper than copper. |

| Magnalium | Alloy | Aircraft Parts | Alloy of magnesium (5%) and aluminium (95%).Stronger than aluminium but still low density. |

CH165: Calculating and converting between gdm-3 and moldm-3

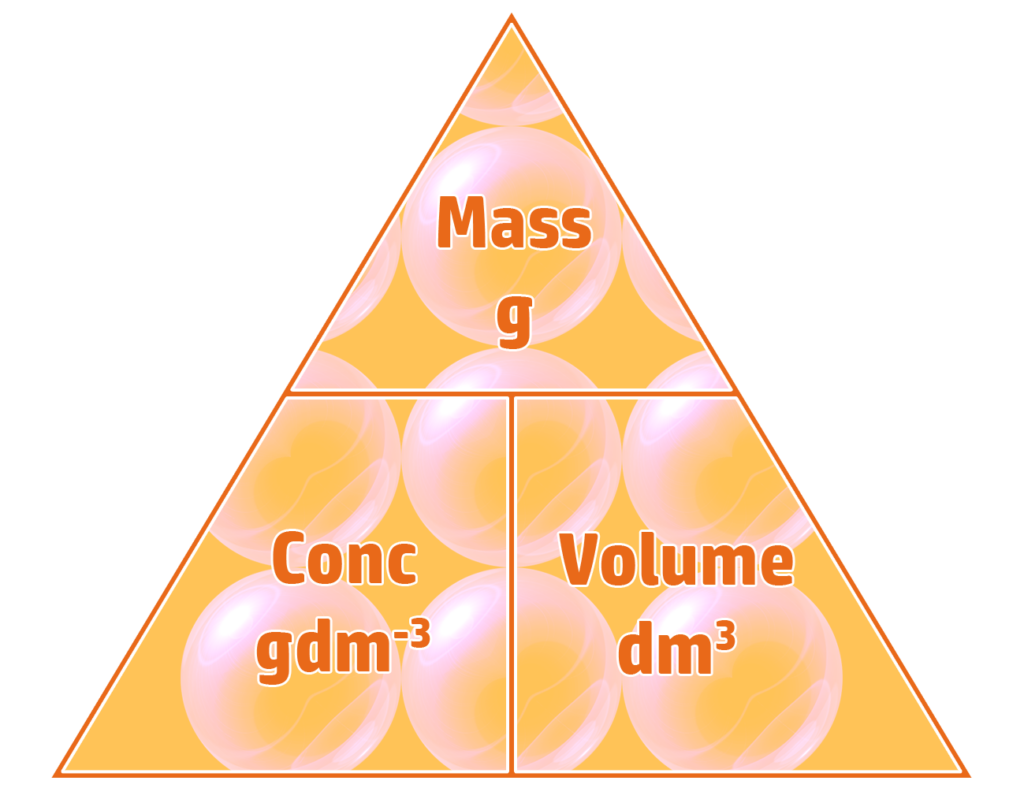

Part 1: Calculating Concentration in gdm-3

To calculate the concentration of a solution in gdm-3, you simply divide the mass (g) by the volume (dm3).

Example: 20g of NaOH is dissolved in 750cm3 of water. Calculate the concentration in gdm-3.

- Volume = 750cm3 ÷ 1000 = 0.75dm3

- Concentration = mass ÷ volume

- Concentration = 20g ÷ 0.75dm3 = 26.7gdm-3

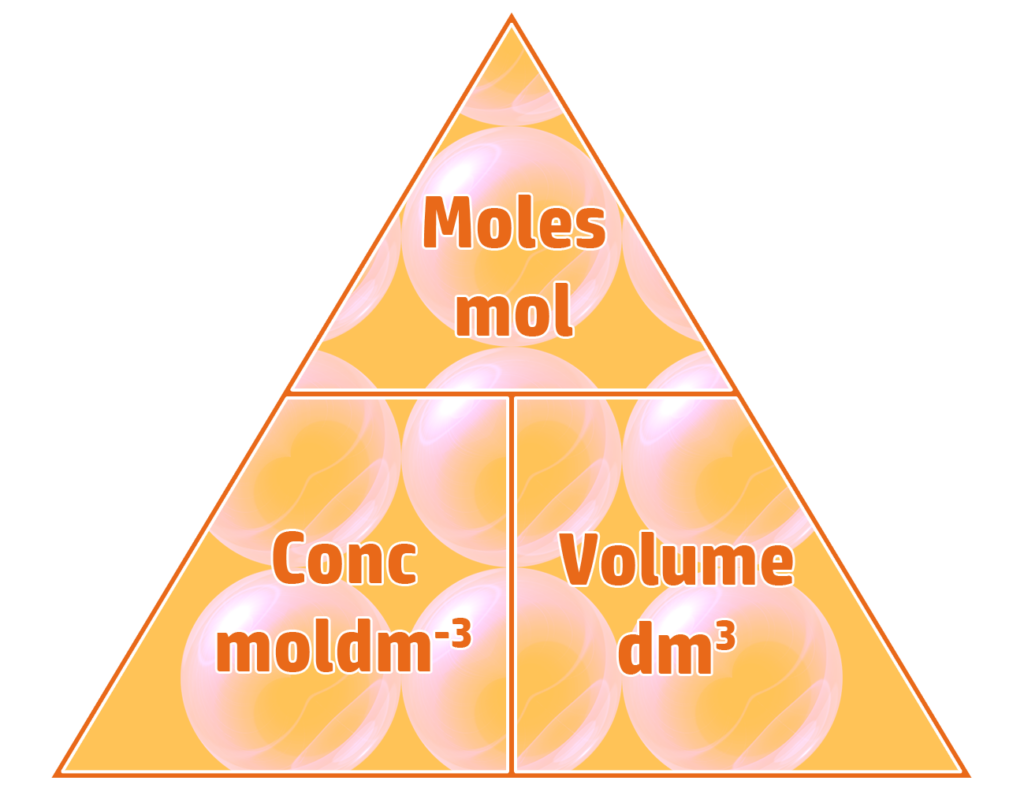

Part 2: Calculating Concentration in moldm-3

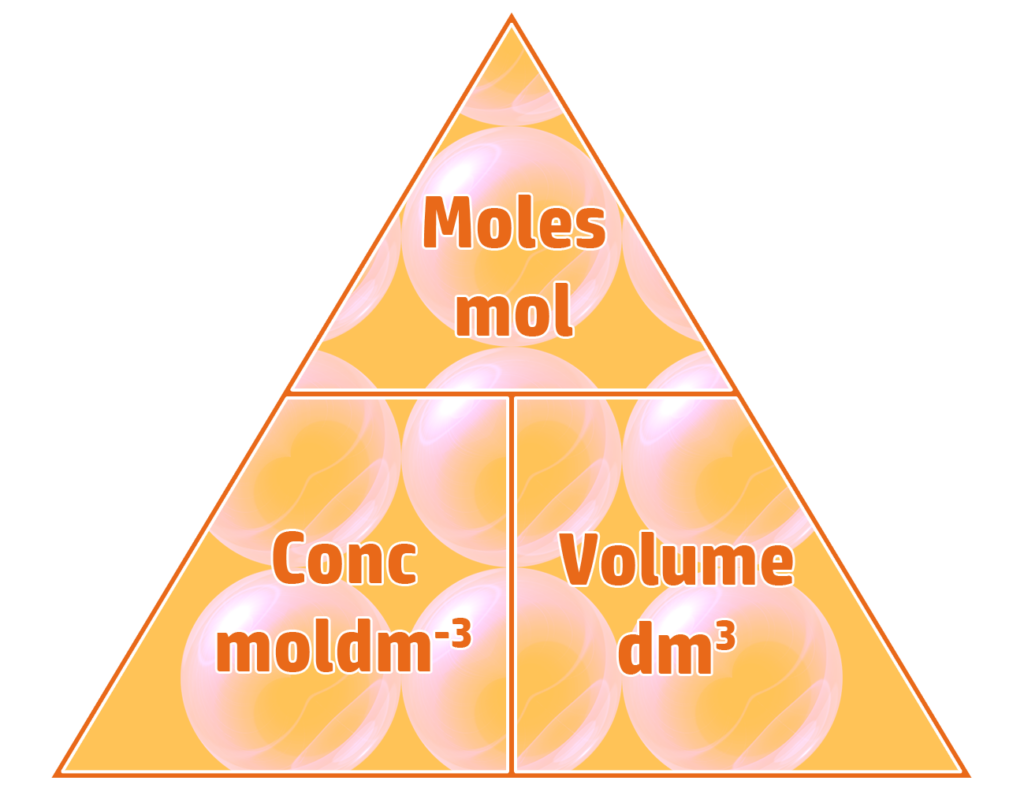

To calculate the concentration of a solution in moldm-3 you divide the moles (see CH86) by the volume (dm3).

Example: 0.5 moles of NaOH are dissolved into 250cm3 of water. Calculate the concentration of the sodium hydroxide solution formed in moldm-3

- Volume = 250cm3 ÷ 1000 = 0.25dm3

- Concentration = moles ÷ volume

- Concentration = 0.5mol ÷ 0.25dm3 = 2moldm-3

Part 3: Converting between gdm-3 and moldm-3

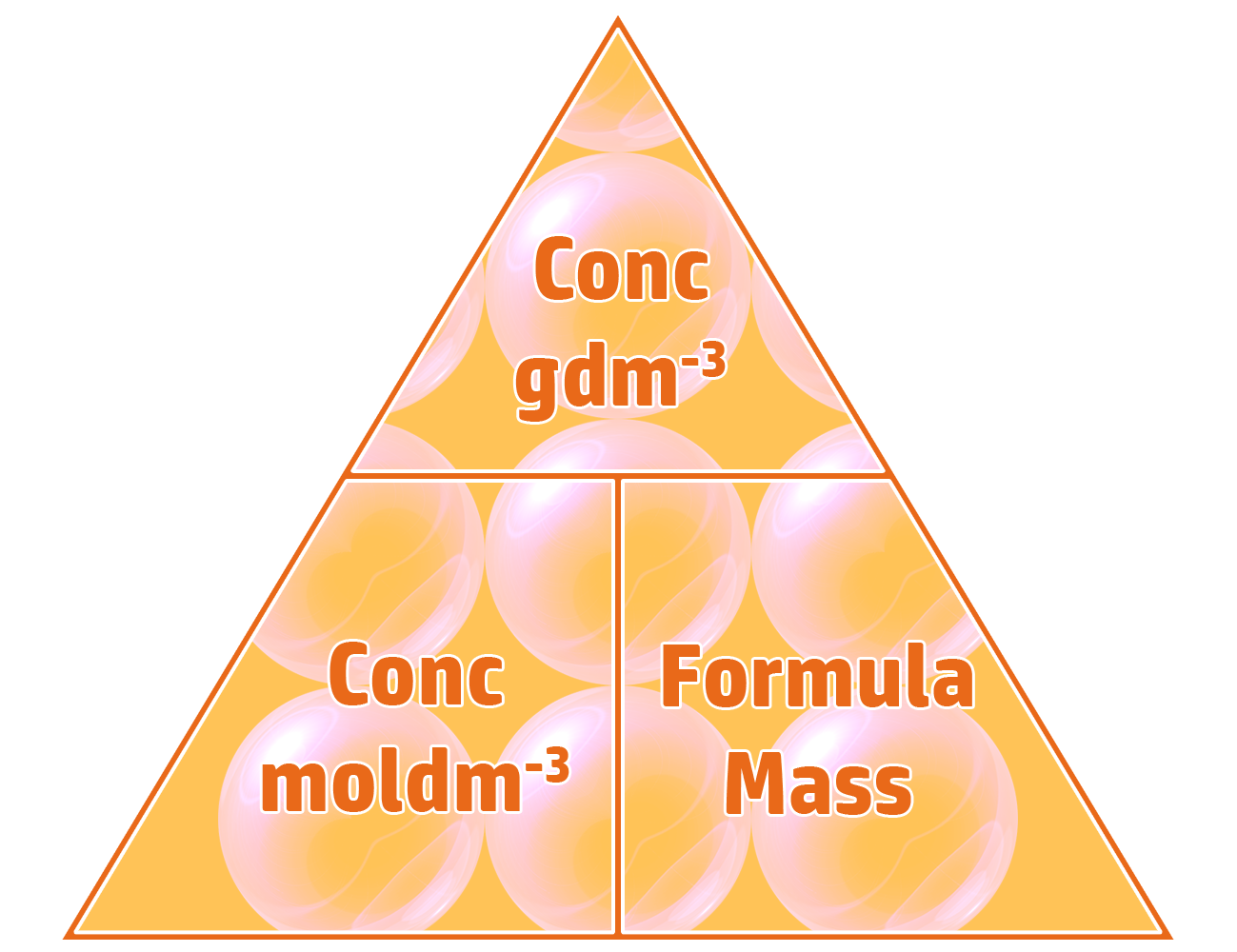

If you know either the concentration in gdm-3 or moldm-3, as well as the formula of the substance, you can convert between gdm-3 and moldm-3 and back using the triangle on the left.

Example: A 26.7gdm-3 solution of sodium hydroxide, NaOH, is produced by dissolving 20g of sodium hydroxide in 0.75dm3 of water. Calculate the concentration in moldm-3. (Ar: Na = 23, O = 16, H = 1)

Step 1: Calculate the Relative Formula Mass, Mr (CH78)

- You have one Na, so 1x23=23

- You have one O, so 1x16=16

- You have one H, so 1x1=1.

- Therefore the Mr is 23+16+1 = 40

Step 2: moldm-3 = gdm-3 ÷ formula mass.

- Concentration = 26.7gdm-3 / 40 = 0.67mol/dm-3

CH166: Core Practical: Carrying out and analysing an Acid-Alkali Titration

How to find an unknown concentration using a titration:

Example: It takes 20cm3 of hydrochloric acid to completely neutralise 25cm3 of 0.1moldm-3 sodium hydroxide.

HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H2O

Explain how to carry out the titration and calculate the concentration of the acid.

Part 1: The Titration

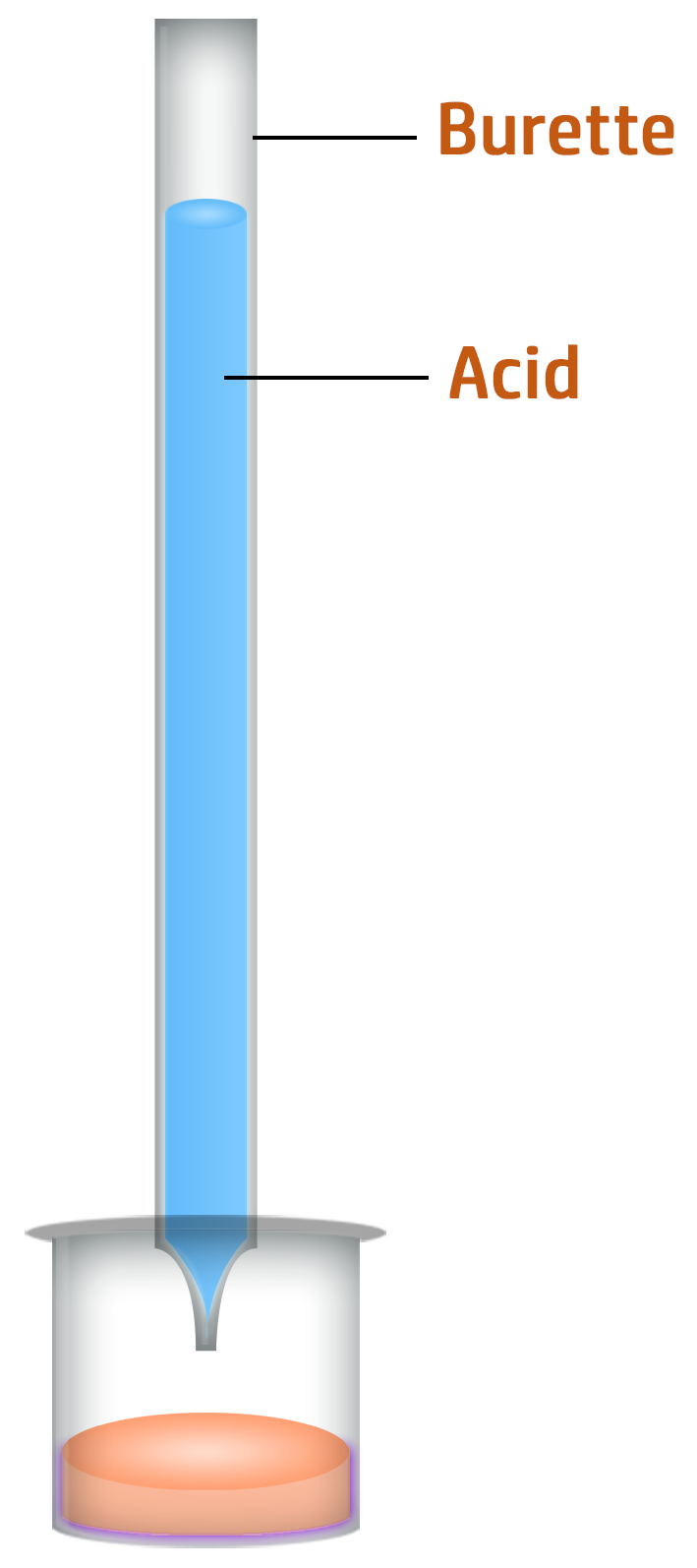

Key Steps: Burette → Pipette → Indicator → End Point → Concordant

- Fill a burette to the 0.0cm3 line with hydrochloric acid.

- Add 20cm3 of your alkali (sodium hydroxide) into a conical flask using a pipette.

- Add a few drops of phenolphthalein indicator - the alkali will turn pink.

- When close to the end point, add the acid drop by drop until the indicator changes from pink to colourless.

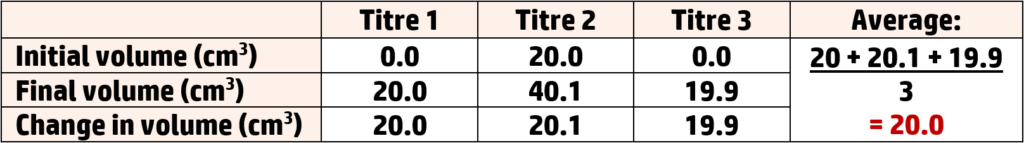

- Repeat the experiment to collect concordant data. Three results should be within 0.2cm3 of each other.

- Take the average. Add all three results up and divide by 3.

Part 2: The results

Part 3: The Calculation (see CH167)

Step 1: Convert the volume for both solution into dm3.

- NaOH: 25cm3 ÷ 1000 = 0.025dm3

- HCl: 20cm3 ÷ 1000 = 0.020dm3

Step 2: Work out the moles of sodium hydroxide (moles = concentration x volume)

- Moles of NaOH: 0.1moldm-3 x 0.025dm3 = 0.0025mol

Step 3: Work out the moles of hydrochloric acid :

- The ratio is 1:1 (1xNaOH to 1xHCl) so you have 0.0025mol of hydrochloric acid.

Step 4: Calculate the concentration of hydrochloric acid

- Concentration of HCl = moles of HCl ÷ volume of HCl

- Concentration of HCl = 0.0025mol ÷ 0.020dm3 = 0.125moldm-3

Improving Accuracy:

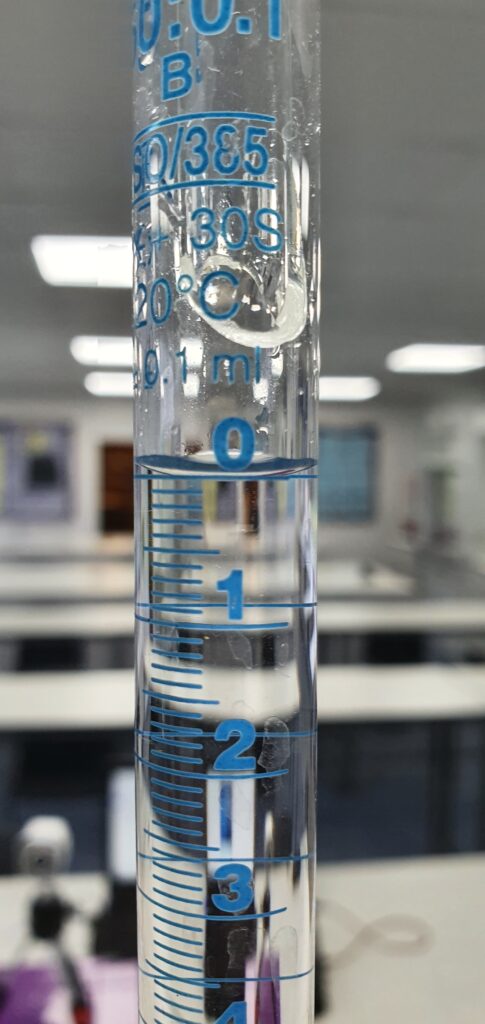

- Burettes / pipettes are more accurate than measuring cylinders.

- Each division on a burette is worth 0.1cm3. This allows us to get a much more accurate reading of a liquid.

- Measure from the bottom of the meniscus line.

- Always measure from the bottom of this curve (see right) to get a more accurate measurement.

CH167: Calculating unknown concentrations from titrations (H)

Example: It takes 20cm3 of lithium hydroxide to completely neutralise 10cm3 of 0.2moldm-3 hydrochloric acid. Calculate the concentration of lithium hydroxide in moldm-3.

LiOH + HCl → LiCl + H2O

Step 1: Convert the volume for both solution into dm3.

- Lithium Hydroxide: 20cm3 ÷ 1000 = 0.02dm3

- Hydrochloric acid: 10cm3 ÷ 1000 = 0.01dm3

Step 2: Work out the moles of hydrochloric acid:

- Moles = concentration x volume

- Moles: 0.2moldm-3 x 0.01dm3 = 0.002mol

Step 3: Work out the moles of lithium hydroxide (here, the ratio is 1:1, so it is the same).

Step 4: Calculate the concentration of lithium hydroxide:

- Concentration = moles ÷ volume

- Concentration = 0.002mol ÷ 0.02dm3 = 0.1moldm-3

CH168: Calculating Theoretical Yields and Percentage Yields

Key word definitions:

- Actual Yield: The mass of a desired product actually produced in a chemical reaction.

- Theoretical Yield: The maximum calculated mass that could be produced.

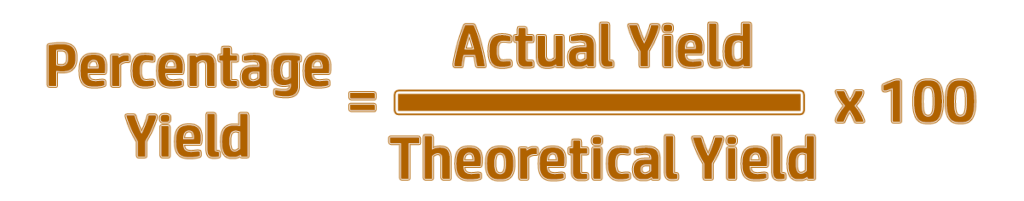

- Percentage Yield: A measure of how much product you actually make in a chemical reaction compared to how much you should make in theory, expressed as a percentage.

Example: In a chemical reaction, 5.3g of sodium carbonate is reacted with excess hydrochloric acid. It was calculated that 5.85g of sodium chloride should be produced, but only 4.2g of sodium chloride was actually formed. Calculate the percentage yield for the reaction.

- Percentage yield = Actual Yield ÷ Theoretical Yield x 100.

- Percentage yield = 4.2g ÷ 5.85g x 100 = 71.8%

You might also be asked to calculate the theoretical yield - this is the same as a maximum mass calculation (see CH83)

CH169: Why is % Yield less than 100%

It is very rare that a reaction produces 100% yield. There are three main reasons for this:

- Some of the products is lost when transferred between containers.

- Side reactions may have occurred.

- The reaction may not have finished. (One of the reactants may have run out.)

If the yield is ever above 100%, it is normally because there is still water left in the product.

CH170: Calculate Atom Economy

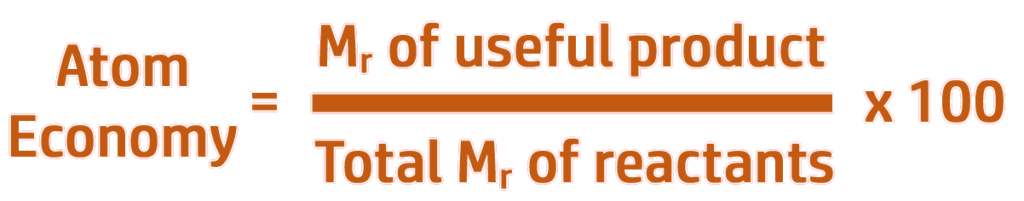

Atom Economy is the percentage of mass converted into useful products and is calculated using the equation on the right.

Example: Ammonium chloride reacts with calcium hydroxide to form ammonia, calcium chloride and water. Work out the atom economy for the formation of calcium chloride in this reaction. (Ar: N = 14, H = 1, Cl = 35.5, Ca = 40, O = 16)

2NH4Cl + Ca(OH)2 → 2NH3 + CaCl2 + 2H2O

Step 1: Find out the formula mass (CH78) for calcium chloride, CaCl2.

- 1 x Ca = 1 x 40 = 40

- 2 x Cl = 2 x 35.5 = 71

- Relative Formula Mass = 40 + 71 = 111.

Step 2: Find out the total formula mass of all of the products combined:

- 2NH3: 2 x (14 + 3) = 34

- 2H2O: 2 x (2 + 16) = 36

- Total formula mass of products = 34 + 36 + 111 = 181

Step 3: Use these two values to calculate the percentage of useful products:

- Atom Economy = formula mass of useful product (calcium chloride) ÷ total formula mass of all products x 100

- Atom economy = 111 ÷ 181 x 100 = 61.3%

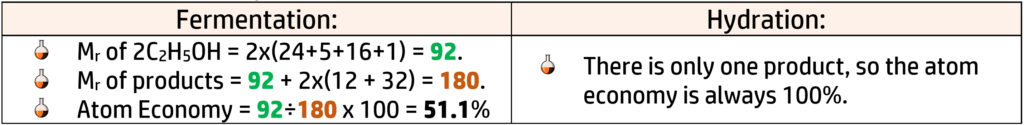

CH171: Evaluate different Reaction Pathways to suggest a suitable reaction

To make any chemical, you want to maximise profit, whilst making a product quickly and in the safest way possible. To do this, you should look at atom economy and any other information to decide which the best pathway is.

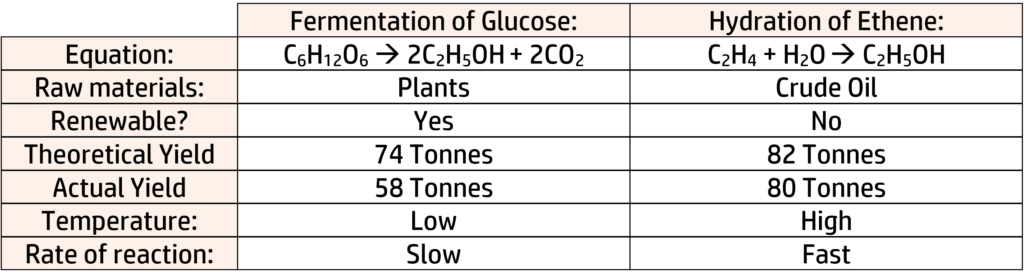

Example: Ethanol can be produced by fermentation of glucose or hydration of ethene. Use the information below to evaluate which reaction should be used:

From the above you can work out the following:

Atom Economy (CH170)

Percentage Yield (CH168)

- Fermentation: (58 ÷ 74) x 100 = 78.4%

- Hydration: (80 ÷ 82) x 100 = 97.6%

Raw Materials:

- Fermentation uses plants, which is renewable and carbon neutral.

- Hydration uses crude oil, which is non-renewable and produces a greenhouse gas.

Other Information:

- Fermentation is a slow process, but can be run at much lower temperatures (which is cheaper).

- Hydration is much faster but must be done at high temperatures. This will use a lot of energy.

Conclusion:

There isn’t always one correct answer, so as long as you back up your conclusion with facts/calculations from above, you will do well:

E.g., I would go with hydration of ethene because it has 100% atom economy, as well as a much higher percentage yield. The reaction is fast but will use a lot of energy and is non-renewable, meaning we will run out of crude oil.

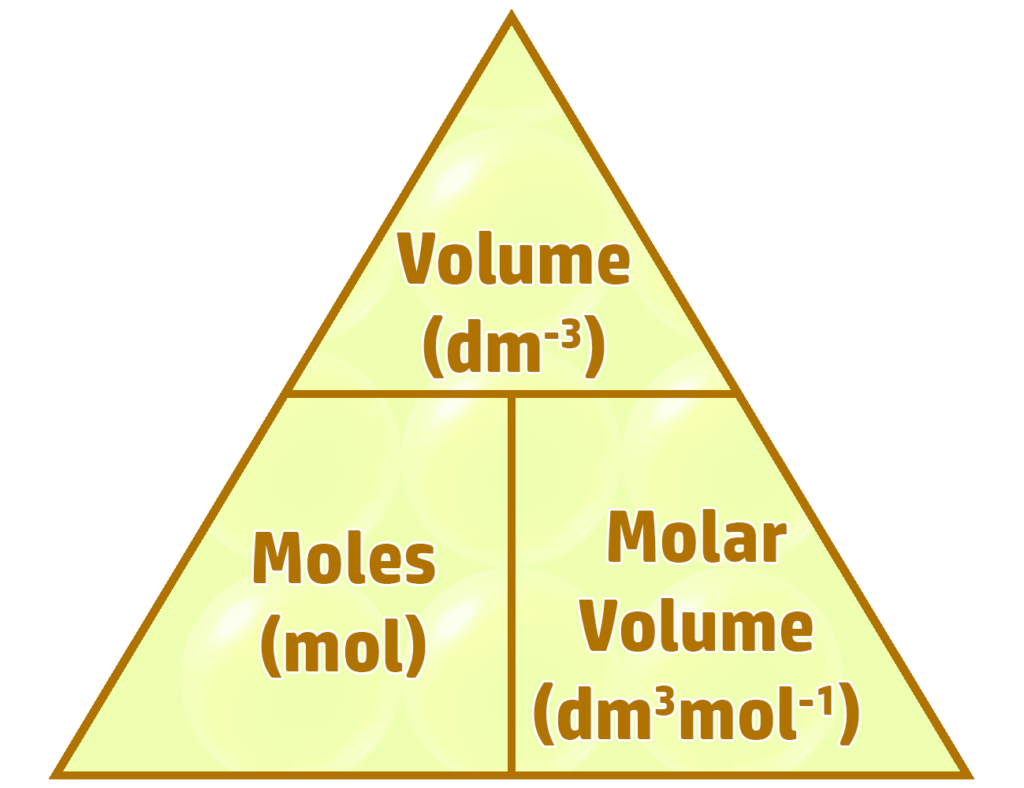

CH172: Avogadro's Law and Gases

The molar volume is the volume of a gas when you have one mole of molecules.

At room temperature (20oC) and pressure (1atm), the

molar volume for 1 mole is always 24dm3mol-1.

You can use this to work out masses and volumes for any balanced equation:

Example 1: Calculate the volume of 0.50 mol of oxygen at room temperature & pressure. (Molar volume = 24dm3mol-1)

- Volume = moles x molar volume

- = 0.5 x 24 = 12dm3

Example 2: In an experiment, hydrogen gas is made by reacting 20.0g of sodium with excess water. Calculate the maximum volume of hydrogen that could be formed.

2Na (s) + 2H2O(l) → 2NaOH(s) + H2 (g)

- Step 1: Find out the formula mass (CH78) for one sodium = 23

- Step 2: Find out the moles (CH86) for sodium = mass ÷ Mr = 20 / 23 = 0.870 moles

- Step 3: The ratio of sodium to hydrogen is 2:1, so you have 0.87/2 = 0.435 moles of hydrogen.

- Step 4: Volume = moles of H2 x molar volume = 0.435 moles x 24 = 10.4dm3

CH173: Molar Volume Calculations

Avogadro’s law states that if the temperature and pressure are the same,the volume will be the same if you have the same number of molecules. You can use this to work out the volumes from balanced equations:

Example: 200dm3 of hydrogen reacts with oxygen to form water vapour. What volume of oxygen would completely react with the hydrogen?

2H2 (g) + O2 (g) → 2H2O(g)

The ratio of moles between hydrogen and oxygen is 2:1 – so the volume of oxygen is half of the volume of hydrogen:

- 200dm3 / 2 = 100dm3.

The volume of water produced would be 200dm3 because the ratio is now 2:2.

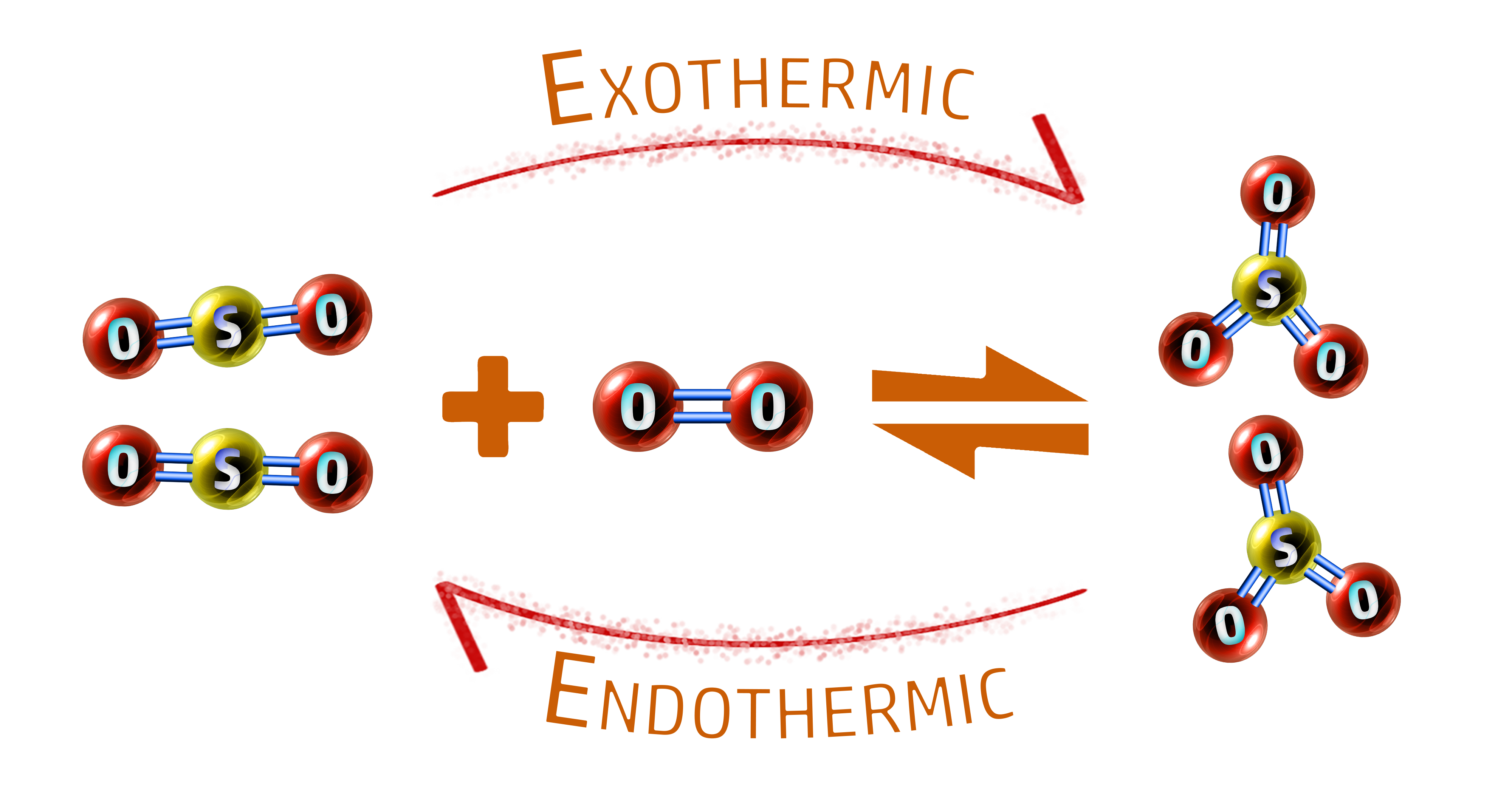

CH174: Explain the factors that affect equilibrium

Example: Sulfur trioxide is made by reacting sulfur dioxide with oxygen. It is a reversible reaction. The forward reaction is exothermic.

2SO2 + O2 ⇌ 2SO3

Explain the effects of temperature, concentration, pressure and a catalyst on the position of equilibrium in the formation of sulfur trioxide.

Temperature:

- Increasing the temperature favours the endothermic reaction.

- In the reaction above, the backwards reaction is endothermic so equilibrium will shift to the left.

- This means increasing the temperature will give a lower yield of sulfur trioxide, SO3.

- The yield of the reactants (SO2 & O2) would increase.

- The reason we increase the temperature is because we get that (smaller) yield much faster than at lower temperatures.

Concentration:

- If you increase the concentration of reactants, there will be more frequent collisions.

- This will move the equilibrium to the right and give you a larger yield of ammonia.

Pressure:

- Increasing the pressure favours the side with less molecules.

- In the reaction above, there are three molecules on the left (one O2 molecule and two SO2 molecules) and two molecules on the right (two SO3 molecules).

- Therefore, increasing the pressure will move equilibrium to the right (the side with the least molecules) and increase the yield of sulfur trioxide.

Catalyst:

- Using a catalyst speeds up the rate of attainment of equilibrium, but does not affect the position of equilibrium.

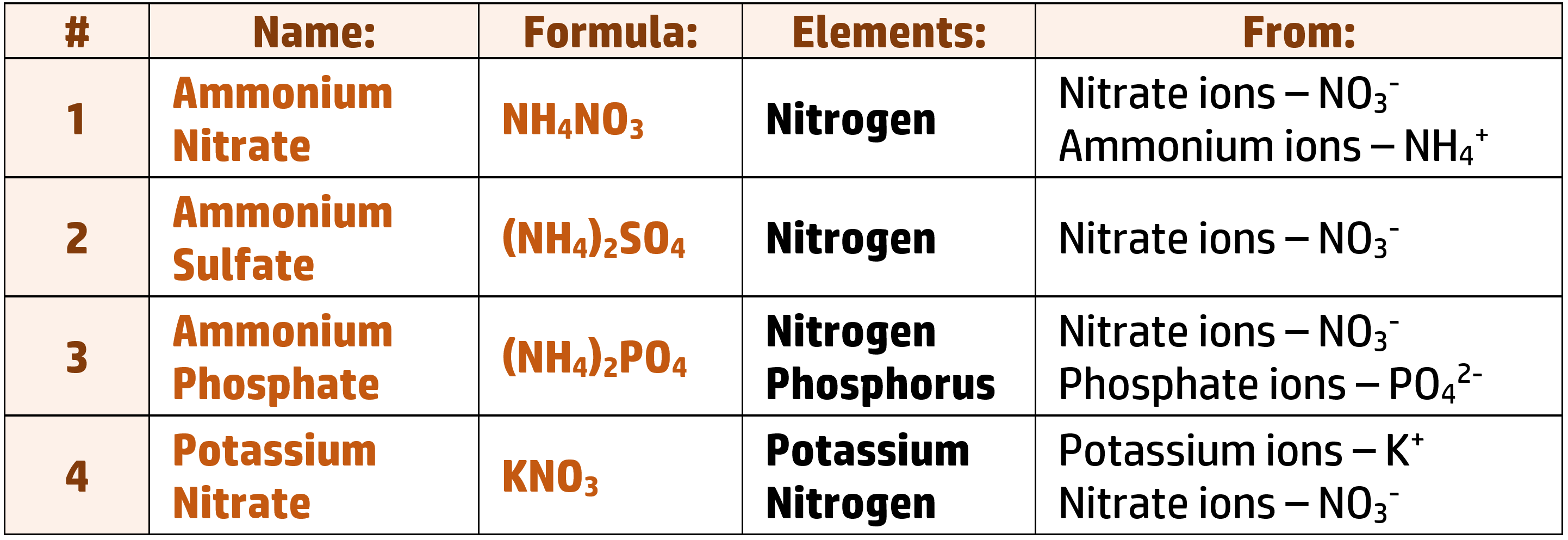

CH175: Describe the importance of fertilisers

When plants grow, they absorb minerals from the soil. Over time, the soil can become mineral deficient which can stop plants from growing – or cause mineral deficiency diseases in the plants. Farmers get round this by using fertilisers.

Fertilisers contain three key minerals: Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium:

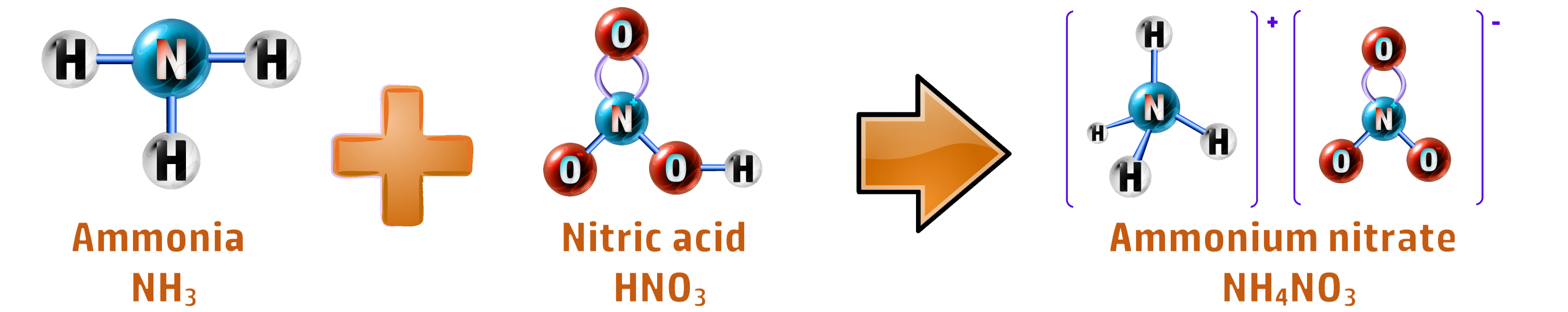

CH176: Describe the formation of ammonium nitrate

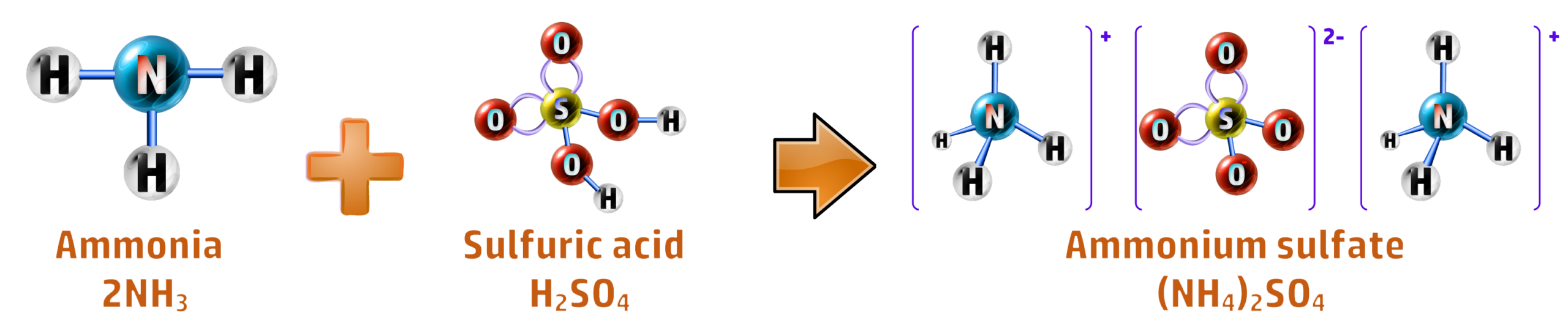

CH177: Describe the steps necessary to produce ammonium sulfate

Ammonium sulfate can be produced both in the Science labs (batch production) and on a large scale (continuous production).

Batch Production: In the lab, it is as simple as a titration between ammonia solution and sulfuric acid, followed by crystallisation:

Batch processes are much slower than large scale continuous processes, so are not good for making large amounts of the fertiliser.

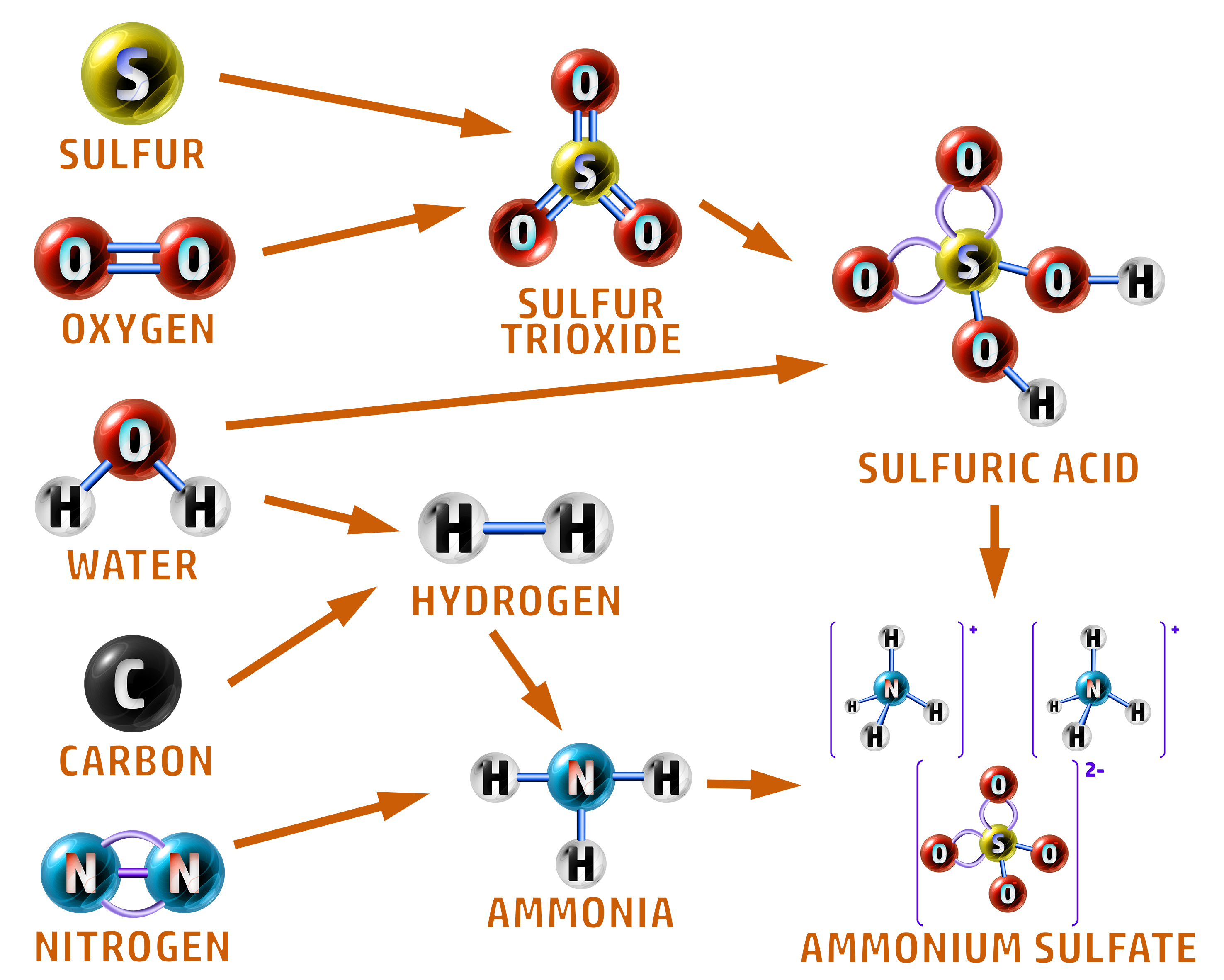

Continuous Processes: In industry, when producing on a larger scale, there are several steps:

The raw materials are all added continuously:

- Sulfur and oxygen react to form sulfur trioxide.

- Water and sulfur trioxide then form sulfuric acid.

- Water and carbon are used to make hydrogen.

- Hydrogen and nitrogen react to form ammonia (Haber Process).

- Ammonia and sulfuric acid react to form ammonium sulfate.

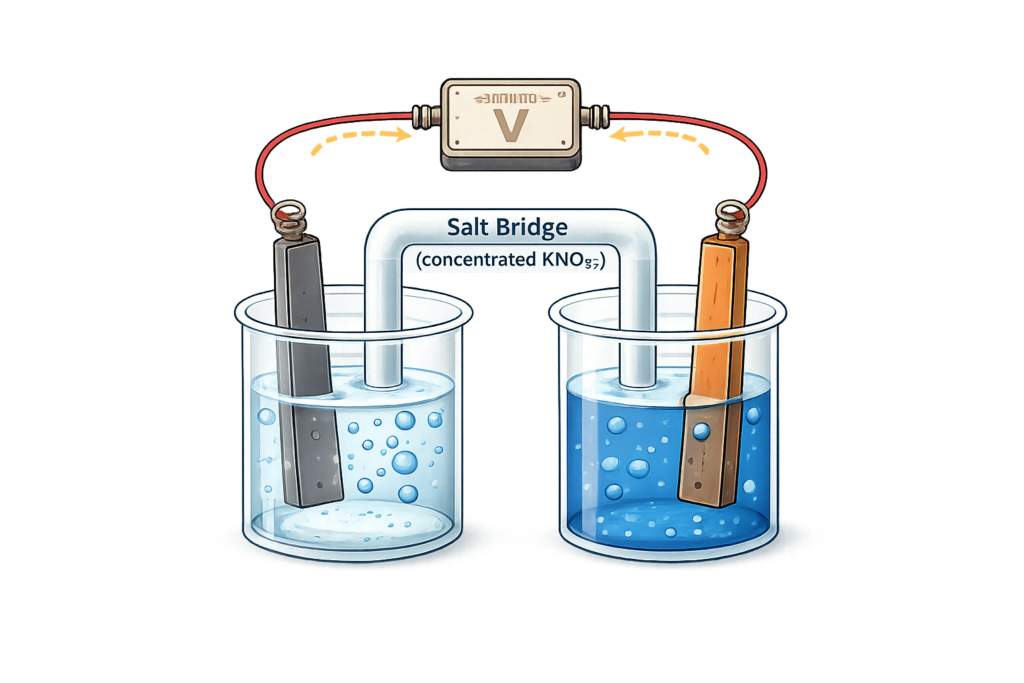

CH178: Describe what a chemical cell is

Chemical cells – such as everyday batteries – produce a voltage when a chemical reaction occurs.

The voltage will start high, then start to decrease until it lowers to zero. At this point, the device will stop working.

They contain two parts:

- Two different metals with solutions of their salts

- A salt bridge to move the ions between the two parts of the cell.

CH179: Explain how a hydrogen fuel cell works

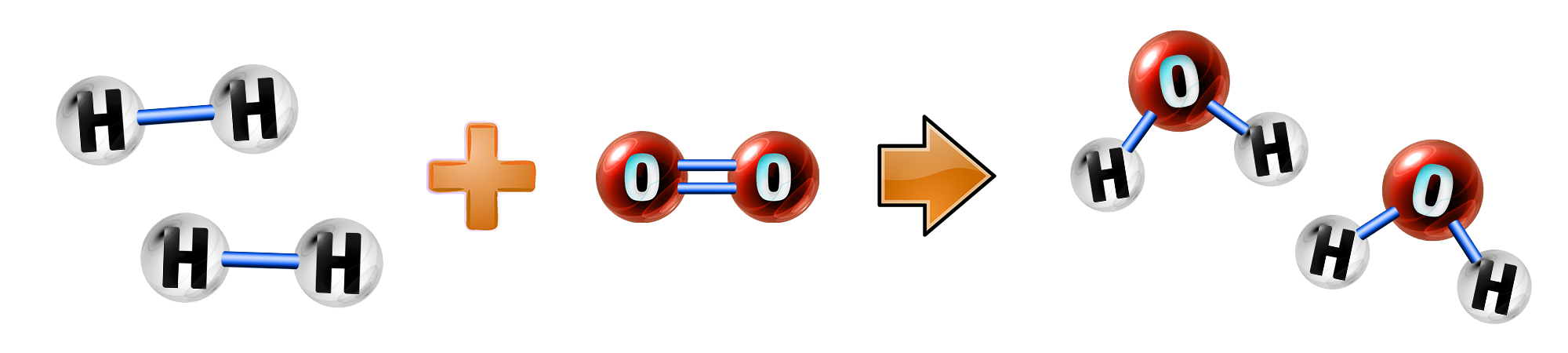

A fuel cell is made up of hydrogen (from fuels) and oxygen (from air)

During the reaction, hydrogen loses electrons (oxidation) to form hydrogen ions:

2H2 → 4H+ + 4e-

The hydrogen ions then react with oxygen, gain electrons (reduction) and form water:

4H+ + 4e- + O2 → 2H2O

CH180: Evaluate the advantages of using a fuel cell instead of fossil fuels

| Advantages of Fuel Cells: | Disadvantages of Fuel Cells: |

|---|---|

| More efficient than using petrol | Hydrogen is a gas – so it takes more space to store |

| No moving parts means less energy lost due to friction | Hydrogen is explosive – so it is harder to store |

| Less reaction steps means less heat lost | Hydrogen is produced from hydrocarbons or electrolysis – both of which use fossil fuels and give off carbon dioxide. |

| No pollutants such as CO2, NO2, SO2 and CO |